Detecting and Responding to MongoBleed (CVE-2025-14847) with Tuskira

Why MongoBleed Breaks Traditional Security Models

And What Happens When Decision Quality Is Engineered Back In

MongoBleed, tracked as CVE-2025-14847, appears to be a routine database vulnerability on paper. In practice, it’s a quiet stress test of modern security systems and how often they mistake normalcy for safety. The flaw demands almost nothing from an attacker. Just network access and a message that looks ordinary enough to be accepted but malformed enough to fail silently. In most environments, nothing visibly breaks. MongoDB keeps running. Applications continue serving traffic. There is no clean exploit signature, no crash, and often no log entry that clearly signals something is wrong.

What appears instead are symptoms that rarely trigger alarm on their own. A handful of odd errors. A momentary slowdown blamed on load. Then thousands of nearly identical events pile up in the background, indistinguishable from the noise generated by complex systems every day. To scanners, to SIEMs, and to humans watching dashboards glow red and yellow, it doesn’t look like an attack. It looks routine, and that’s the failure MongoDB Bleed exposes. Security tools can tell you which versions are vulnerable, but not whether they are reachable. SOC teams see volume without meaning and are pushed to react before answering the only question that matters: Is this actually exploitable right now?

Automation only accelerates the mistake, treating alerts as truth before proving they’re warranted. MongoBleed strips away the illusion that visibility equals control and forces teams to confront whether they can prove what is real.

That’s where Tuskira starts.

Step 1: Determining Whether MongoBleed Is Exploitable & Defensible

Tuskira treats CVSS scores as inputs, not conclusions. For MongoBleed, exploitability is determined by correlating context most tools never combine:

Asset and Configuration Context

- MongoDB version and patch level.

- Whether zlib compression is enabled.

- Deployment model, ownership, and business criticality.

Network Reachability

- Whether MongoDB listeners are reachable from the internet.

- Which internal tiers can access them.

- What load balancers, NAT layers, or service meshes sit in between.

Compensating Controls

- Segmentation and security groups.

- Proxy, WAF, or mesh enforcement.

- Identity-based access controls and service authentication.

Outcome:

The result is an assertion backed by evidence.

- This MongoDB instance is vulnerable but not reachable

or

- This MongoDB instance is vulnerable, reachable, and unprotected

At that moment, scanner-driven noise collapses. Most alerts stop mattering. Only a small number of assets remain relevant. And once exploitability is established, the next question becomes unavoidable.

How would an attacker actually reach it?

This view shows Tuskira’s VM Copilot cutting through alert noise to confirm the real impact of CVE-2025-14847 by correlating vulnerability data, IOCs, and network reachability. By visualizing the full attack path from external entry point to MongoDB, it isolates the single exposed asset and enables a precise handoff to remediation.

Step 2: Validating the Attack Path

MongoBleed exploitation requires only one prerequisite: network access to the MongoDB protocol handler. That is the entire attack. Everything else is an implementation detail.

What Tuskira does differently is prove whether that access actually exists. Within the digital twin, Tuskira reconstructs the real attack path that a malformed message would traverse in the deployed environment. That path often looks mundane:

External entry point

→ Load Balancer

→ Target group

→ Application compute

→ MongoDB Service

Only after that infrastructure path is confirmed does Tuskira validate the protocol-level reality beneath it. Can malformed compressed messages reach the parsing logic? Does authentication block the path? Do upstream controls normalize or reject the payload before it ever reaches zlib or BSON handling?

With that context, MongoBleed stops being “theoretically severe” and becomes something far more dangerous or far less urgent: provably exploitable or provably blocked.

Without this step, teams are guessing.

Step 3: Determining Whether Exploitation Is Already Underway

MongoBleed detection is behavioral, not signature-based. Tuskira correlates telemetry across application, network, and control layers to determine whether observed behavior represents active abuse or benign failure.

At the application layer, this shows up as clusters of InvalidBSON parsing errors and anomalous slow-query behavior that rarely trigger alerts on their own. At the network layer, it appears as short-lived connections and abnormal compressed-payload patterns that are indistinguishable from routine traffic. Across controls, Tuskira evaluates whether existing IDS or NDR detections fired, were suppressed, or failed to interrupt the behavior entirely.

This correlation answers a question most security programs never get to ask clearly. Is this noise, misconfiguration, or exploitation? Only once that question is answered does escalation make sense.

Step 4: Suppressing Noise Before It Reaches the SOC

MongoBleed attacks often generate thousands of nearly identical log events. Without validation, this creates alert storms, analyst fatigue, and misprioritized incidents.

Tuskira suppresses noise upstream by deduplicating repetitive malformed requests, collapsing thousands of identical events into a single validated incident, and suppressing signals from assets proven non-exploitable.

Only validated exploitation behavior is escalated. The SOC sees fewer alerts, but far higher certainty.

Step 5: From Decision to Fix Without Guesswork

Once exploitability and impact are proven, Tuskira determines the correct response and where to apply it.

- Some cases stop at containment

- Others require mitigation at the control layer

- Only a few justify full remediation.

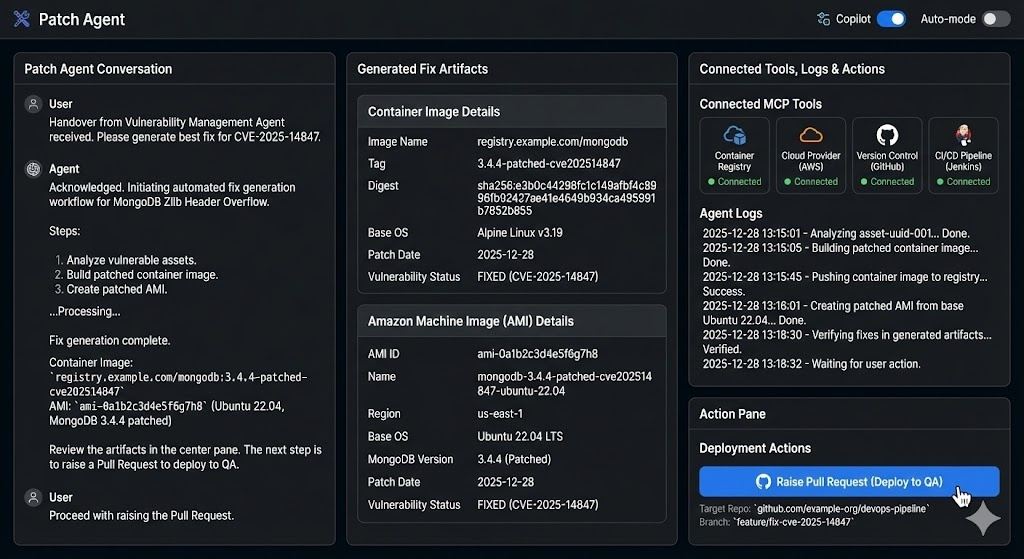

When remediation is required, the Patch Agent takes over. It automates the engineering work most teams still handle manually.

- Patched container images are generated and pushed to the registry.

- Patched Amazon Machine Images are built and made deployment-ready.

- Every step is logged, verified, and auditable.

The workflow ends not with a vague “resolved” status, but with a concrete action: a pull request raised to deploy the fix into QA.

After exploitability is confirmed, Tuskira’s Patch Agent automatically builds patched container images and AMIs, logging every step for verification. The remediation concludes with a pull request to deploy the fix, providing evidence-backed closure rather than a generic “resolved” status.

Step 6: Validating Closure

After mitigation or remediation, Tuskira re-validates the environment.

- Attack paths are re-tested.

- Malformed messages are confirmed to be blocked.

- Compensating controls are verified to behave as expected.

- Evidence of risk reduction is recorded.

MongoBleed stops being a fire drill. It becomes a closed, validated security event.

Why This Matters

Traditional advisories explain how to hunt for MongoBleed. Tuskira exists to prove whether the hunt is even necessary.

MongoBleed represents a growing class of protocol-level, behavior-driven vulnerabilities that are poorly logged by default and easy to exploit once reachable.

These flaws don’t announce themselves cleanly. They don’t fit neatly into scanner findings or alert-based workflows. In that world, security programs built on lists, scores, and alert volume will continue to react late and respond without certainty.

So the problem isn’t detection so much as it is decision quality.

Tuskira was built for this reality. It validates what is actually exploitable, suppresses what never mattered, and grounds every response decision in evidence. The result is fewer wrong decisions, made earlier, with proof that risk has actually been reduced.